Elasticity Measures The Responsiveness Of

5.3 Price Elasticity of Supply

Learning Objectives

- Explain the concept of elasticity of supply and its calculation.

- Explain what it means for supply to be price inelastic, unit price elastic, price elastic, perfectly price inelastic, and perfectly price rubberband.

- Explain why time is an important determinant of cost elasticity of supply.

- Apply the concept of price elasticity of supply to the labor supply curve.

The elasticity measures encountered then far in this affiliate all relate to the demand side of the market. It is also useful to know how responsive quantity supplied is to a change in cost.

Suppose the need for apartments rises. There will be a shortage of apartments at the former level of apartment rents and pressure level on rents to rise. All other things unchanged, the more responsive the quantity of apartments supplied is to changes in monthly rents, the lower the increase in rent required to eliminate the shortage and to bring the market dorsum to equilibrium. Conversely, if quantity supplied is less responsive to price changes, price will have to ascent more than to eliminate a shortage caused past an increase in demand.

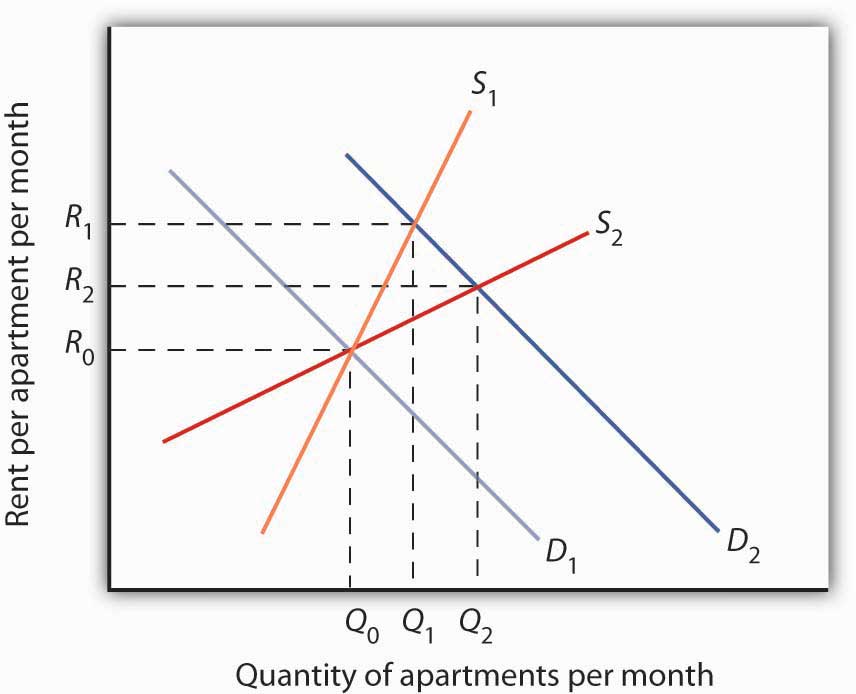

This is illustrated in Figure 5.10 "Increase in Apartment Rents Depends on How Responsive Supply Is". Suppose the rent for a typical apartment had been R 0 and the quantity Q 0 when the demand curve was D 1 and the supply bend was either Southward i (a supply bend in which quantity supplied is less responsive to toll changes) or S 2 (a supply curve in which quantity supplied is more responsive to price changes). Note that with either supply curve, equilibrium price and quantity are initially the same. At present suppose that demand increases to D 2, perhaps due to population growth. With supply bend S 1, the price (rent in this instance) will rise to R one and the quantity of apartments will rise to Q 1. If, however, the supply curve had been S ii, the rent would only have to ascent to R 2 to bring the market back to equilibrium. In addition, the new equilibrium number of apartments would be higher at Q 2. Supply bend South 2 shows greater responsiveness of quantity supplied to price change than does supply curve S 1.

Figure 5.10 Increase in Apartment Rents Depends on How Responsive Supply Is

The more responsive the supply of apartments is to changes in price (hire in this case), the less rents rise when the demand for apartments increases.

We measure the price elasticity of supply (eastS ) as the ratio of the per centum change in quantity supplied of a good or service to the percentage change in its toll, all other things unchanged:

Equation 5.6

[latex]e_S = \frac{ \% \: change \: in \: quantity \: supplied}{ \% \: change \: in \: toll}[/latex]

Because toll and quantity supplied usually move in the same management, the price elasticity of supply is commonly positive. The larger the toll elasticity of supply, the more responsive the firms that supply the adept or service are to a cost modify.

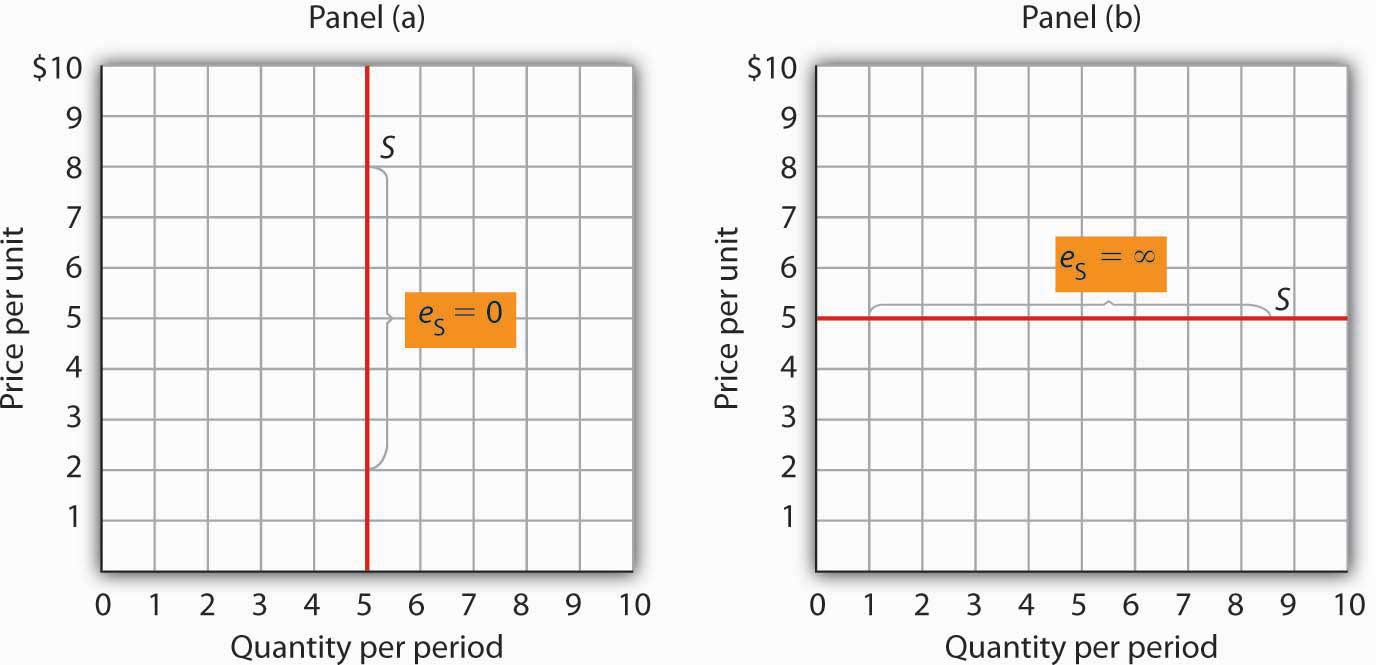

Supply is cost elastic if the price elasticity of supply is greater than i, unit price rubberband if information technology is equal to 1, and price inelastic if it is less than 1. A vertical supply curve, equally shown in Panel (a) of Figure v.11 "Supply Curves and Their Toll Elasticities", is perfectly inelastic; its price elasticity of supply is zilch. The supply of Beatles' songs is perfectly inelastic because the band no longer exists. A horizontal supply curve, as shown in Panel (b) of Figure five.11 "Supply Curves and Their Price Elasticities", is perfectly elastic; its toll elasticity of supply is space. It means that suppliers are willing to supply any amount at a certain toll.

Effigy 5.11 Supply Curves and Their Price Elasticities

The supply curve in Panel (a) is perfectly inelastic. In Panel (b), the supply bend is perfectly elastic.

Time: An Important Determinant of the Elasticity of Supply

Time plays a very of import part in the determination of the price elasticity of supply. Look again at the effect of rent increases on the supply of apartments. Suppose flat rents in a city rise. If we are looking at a supply bend of apartments over a flow of a few months, the rent increment is probable to induce apartment owners to rent out a relatively small number of additional apartments. With the college rents, flat owners may exist more vigorous in reducing their vacancy rates, and, indeed, with more than people looking for apartments to rent, this should exist adequately like shooting fish in a barrel to attain. Attics and basements are easy to renovate and rent out as additional units. In a short period of fourth dimension, however, the supply response is likely to be adequately modest, implying that the price elasticity of supply is adequately low. A supply curve corresponding to a short period of time would await similar S ane in Effigy five.10 "Increase in Apartment Rents Depends on How Responsive Supply Is". Information technology is during such periods that there may exist calls for rent controls.

If the period of fourth dimension nether consideration is a few years rather than a few months, the supply bend is probable to be much more price elastic. Over time, buildings tin can be converted from other uses and new apartment complexes can be built. A supply curve corresponding to a longer menses of time would await like South 2 in Figure v.10 "Increase in Apartment Rents Depends on How Responsive Supply Is".

Elasticity of Labor Supply: A Special Application

The concept of price elasticity of supply can be practical to labor to show how the quantity of labor supplied responds to changes in wages or salaries. What makes this case interesting is that it has sometimes been found that the measured elasticity is negative, that is, that an increase in the wage rate is associated with a reduction in the quantity of labor supplied.

In most cases, labor supply curves have their normal upward gradient: college wages induce people to work more. For them, having the boosted income from working more than is preferable to having more than leisure time. Nonetheless, wage increases may pb some people in very highly paid jobs to cut dorsum on the number of hours they work considering their incomes are already loftier and they would rather take more than time for leisure activities. In this case, the labor supply curve would have a negative slope. The reasons for this phenomenon are explained more than fully in a later chapter.

This chapter has covered a diversity of elasticity measures. All report the degree to which a dependent variable responds to a alter in an independent variable. As nosotros accept seen, the degree of this response tin play a critically important role in determining the outcomes of a broad range of economic events. Table 5.2 "Selected Elasticity Estimates"1 provides examples of some estimates of elasticities.

Tabular array 5.2 Selected Elasticity Estimates

| Production | Elasticity | Product | Elasticity | Production | Elasticity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price Elasticity of Demand | Cross Price Elasticity of Demand | Income Elasticity of Demand | |||

| Crude oil (U.S.)* | −0.06 | Alcohol with respect to price of heroin | −0.05 | Speeding citations | −0.26 to −0.33 |

| Gasoline | −0.1 | Fuel with respect to cost of transport | −0.48 | Urban Public Trust in France and Madrid (respectively) | −0.23; −0.26 |

| Speeding citations | −0.21 | Alcohol with respect to price of food | −0.sixteen | Ground beef | −0.197 |

| Cabbage | −0.25 | Marijuana with respect to price of heroin (similar for cocaine) | −0.01 | Lottery instant game sales in Colorado | −0.06 |

| Cocaine (2 estimates) | −0.28; −1.0 | Beer with respect to price of vino distilled liquor (young drinkers) | 0.0 | Heroin | −0.00 |

| Booze | −0.30 | Beer with respect to price of distilled liquor (immature drinkers) | 0.0 | Marijuana, alcohol, cocaine | +0.00 |

| Peaches | −0.38 | Pork with respect to price of poultry | 0.06 | Potatoes | 0.15 |

| Marijuana | −0.four | Pork with respect to cost of basis beef | 0.23 | Nutrient** | 0.2 |

| Cigarettes (all smokers; two estimates) | −0.4; −0.32 | Ground beef with respect to price of poultry | 0.24 | Clothing*** | 0.three |

| Crude oil (U.S.)** | −0.45 | Ground beefiness with respect to toll of pork | 0.35 | Beer | 0.four |

| Milk (2 estimates) | −0.49; −0.63 | Coke with respect to price of Pepsi | 0.61 | Eggs | 0.57 |

| Gasoline (intermediate term) | −0.five | Pepsi with respect to cost of Coke | 0.lxxx | Coke | 0.threescore |

| Soft drinks | −0.55 | Local television advertising with respect to price of radio ad | ane.0 | Shelter** | 0.7 |

| Transportation* | −0.6 | Smokeless tobacco with respect to price of cigarettes (young males) | 1.ii | Beef (table cuts—not ground) | 0.81 |

| Nutrient | −0.vii | Price Elasticity of Supply | Oranges | 0.83 | |

| Beer | −0.seven to −0.9 | Physicians (Specialist) | −0.3 | Apples | i.32 |

| Cigarettes (teenagers; 2 estimates) | −0.9 to −1.five | Physicians (Primary Care) | 0.0 | Leisure** | 1.4 |

| Heroin | −0.94 | Physicians (Immature male) | 0.2 | Peaches | i.43 |

| Ground beefiness | −1.0 | Physicians (Young female person) | 0.five | Health care** | i.6 |

| Cottage cheese | −1.1 | Milk* | 0.36 | College educational activity | 1.67 |

| Gasoline** | −ane.5 | Milk** | 0.v | ||

| Coke | −1.71 | Child care labor | 2 | ||

| Transportation | −1.9 | ||||

| Pepsi | −2.08 | ||||

| Fresh tomatoes | −ii.22 | ||||

| Food** | −2.3 | ||||

| Lettuce | −2.58 | ||||

| Note: *=short-run; **=long-run | |||||

Primal Takeaways

- The price elasticity of supply measures the responsiveness of quantity supplied to changes in price. It is the percentage change in quantity supplied divided past the percent change in price. It is usually positive.

- Supply is price inelastic if the price elasticity of supply is less than ane; it is unit price elastic if the toll elasticity of supply is equal to 1; and information technology is price elastic if the price elasticity of supply is greater than ane. A vertical supply curve is said to be perfectly inelastic. A horizontal supply curve is said to be perfectly rubberband.

- The cost elasticity of supply is greater when the length of time under consideration is longer because over time producers have more options for adjusting to the change in price.

- When applied to labor supply, the toll elasticity of supply is commonly positive but can be negative. If college wages induce people to piece of work more than, the labor supply curve is upward sloping and the price elasticity of supply is positive. In some very loftier-paying professions, the labor supply curve may have a negative gradient, which leads to a negative price elasticity of supply.

Endeavour It!

In the late 1990s, it was reported on the news that the high-tech industry was worried about being able to find enough workers with computer-related expertise. Job offers for contempo higher graduates with degrees in computer science went with loftier salaries. Information technology was too reported that more undergraduates than ever were majoring in computer science. Compare the price elasticity of supply of figurer scientists at that signal in time to the price elasticity of supply of computer scientists over a longer menstruation of, say, 1999 to 2009.

Example in Signal: A Variety of Labor Supply Elasticities

Figure five.12

Studies support the idea that labor supply is less elastic in high-paying jobs than in lower-paying ones.

For instance, David One thousand. Blau estimated the labor supply of kid-care workers to be very price elastic, with estimated price elasticity of labor supply of about 2.0. This ways that a 10% increment in wages leads to a 20% increase in the quantity of labor supplied. John Burkett estimated the labor supply of both nursing assistants and nurses to be price elastic, with that of nursing assistants to exist 1.ix (very close to that of kid-care workers) and of nurses to be one.one. Note that the price elasticity of labor supply of the higher-paid nurses is a flake lower than that of lower-paid nursing assistants.

In dissimilarity, John Rizzo and David Blumenthal estimated the cost elasticity of labor supply for young physicians (under the age of 40) to be about 0.3. This ways that a ten% increase in wages leads to an increase in the quantity of labor supplied of only about 3%. In addition, when Rizzo and Blumenthal looked at labor supply elasticities past gender, they plant the female physicians' labor supply price elasticity to be a bit higher (at about 0.5) than that of the males (at almost 0.ii) in the sample. Because earnings of female person physicians in the sample were lower than earnings of the male physicians in the sample, this deviation in labor supply elasticities was expected. Moreover, since the sample consisted of physicians in the early phases of their careers, the positive, though pocket-size, toll elasticities were also expected. Many of the individuals in the sample as well had high debt levels, often from educational loans. Thus, the chance to earn more by working more is an opportunity to repay educational and other loans.

In another study of physicians' labor supply that was not restricted to young physicians, Douglas M. Brown establish the labor supply price elasticity for primary care physicians to be close to zero and that of specialists to be negative, at about −0.3. Thus, for this sample of physicians, increases in wages have trivial or no effect on the amount the primary intendance doctors work, while a ten% increase in wages for specialists reduces their quantity of labor supplied past about 3%. Because the earnings of specialists exceed those of primary intendance doctors, this elasticity differential also makes sense.

Sources: David M. Blau, "The Supply of Child Care Labor," Periodical of Labor Economics 11:two (April 1993): 324–347; David M. Brown, "The Rising Cost of Dr.'s Services: A Correction and Extension on Supply," Review of Economics and Statistics 76 (2) (May 1994): 389–393; John P. Burkett, "The Labor Supply of Nurses and Nursing Assistants in the United States," Eastern Economic Journal 31(4) (Fall 2005): 585–599; John A. Rizzo and Paul Blumenthal. "Physician Labor Supply: Practice Income Effects Matter?" Periodical of Health Economics xiii:4 (December 1994): 433–453.

Answer to Endeavour It! Problem

While at a point in time the supply of people with degrees in computer science is very price inelastic, over time the elasticity should rise. That more than students were majoring in informatics lends credence to this prediction. Equally supply becomes more price elastic, salaries in this field should rise more slowly.

aneAlthough close to zero in all cases, the significant and positive signs of income elasticity for marijuana, alcohol, and cocaine suggest that they are normal appurtenances, but significant and negative signs, in the case of heroin, advise that heroin is an junior good. Saffer and Chaloupka (cited beneath) suggest the furnishings of income for all 4 substances might exist affected by education. [Other References listed beneath]

References

Adesoji, O. Adelaja, A. "Price Changes, Supply Elasticities, Manufacture Organization, and Dairy Output Distribution," American Journal of Agricultural Economics 73:ane (February 1991):89–102.

Bar-Ilan, A., and Bruce Sacerdote, "The Response of Criminals and Not-Criminals to Fines," Journal of Police force and Economics, 47:1 (April 2004): 1–17.

Baye, G.R., D.W. Jansen, and J.W. Lee, "Advertisement Furnishings in Complete Need Systems," Applied Economics 24 (1992):1087–1096.

Bhuyan, South., and Rigoberto A. Lopez, "Oligopoly Power in the Food and Tobacco Industries," American Journal of Agricultural Economics 79 (August 1997):1035–1043.

Blau, D. G., "The Supply of Child Care Labor," Journal of Labor Economics 2(11) (April 1993):324–347.

Blundell, R., et al., "What Exercise We Learn About Consumer Demand Patterns from Micro Data?", American Economic Review 83(3) (June 1993):570–597.

Bresson, M., Joyce Dargay, Jean-Loup Madre, and Alain Pirotte, "Economic and Structural Determinants of the Demand for French Transport: An Assay on a Panel of French Urban Areas Using Shrinkage Estimators," Transportation Research: Role A 38:4 (May 2004): 269–285.

Brester, Yard. Due west., and Michael K. Wohlgenant, "Estimating Interrelated Demands for Meats Using New Measures for Footing and Table Cut Beef," American Journal of Agricultural Economics 73 (November 1991):1182–1194.

Brown, D. Grand., "The Ascent Price of Physicians' Services: A Correction and Extension on Supply," Review of Economics and Statistics 76(2) (May 1994):389–393.

Davis, G. C., and Michael K. Wohlgenant, "Demand Elasticities from a Discrete Choice Model: The Natural Christmas Tree Market," Journal of Agricultural Economics 75(iii) (August 1993):730–738.

Ekelund, R. B., S. Ford, and John D. Jackson. "Are Local TV Markets Separate Markets?" International Periodical of the Economics of Business organisation 7:1 (2000): 79–97.

Elzinga, K. One thousand., "Beer," in Walter Adams and James Brock, eds., The Structure of American Industry, 9th ed. (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1995), pp. 119–151.

Farrelly, M. C., Terry F. Pechacek, and Frank J. Chaloupka; "The Affect of Tobacco Command Program Expenditures on Amass Cigarette Sales: 1981–2000," Journal of Health Economics 22:5 (September 2003): 843–859.

Fogel, R. W., "Communicable Up With the Economy," American Economic Review 89(1) (March, 1999):1–21.

Gasmi, F., et al., "Econometric Analysis of Collusive Beliefs in a Soft-Drink Market place," Journal of Economic science and Management Strategy (Summer 1992), pp. 277–311.

Griffin, J. G., and Henry B. Steele, Energy Economic science and Policy (New York: Bookish Press, 1980), p. 232.

Grossman, M., "A Survey of Economical Models of Addictive Behavior," Journal of Drug Issues 28:3 (Summer 1998):631–643.

Grossman, M., "Cigarette Taxes," Public Health Reports 112:4 (July/Baronial 1997): 290–297.

Grossman, M., and Henry Saffer, "Beer Taxes, the Legal Drinking Age, and Youth Motor Vehicle Fatalities," Journal of Legal Studies sixteen(2) (June 1987):351–374.

Hansen, A., "The Tax Incidence of the Colorado State Lottery Instant Game," Public Finance Quarterly 23(3) (July, 1995):385–398.

Heien, D., and Cathy Roheim Wessells, "The Need for Dairy Products: Structure, Prediction, and Decomposition," American Journal of Agriculture Economics (May 1988):219–228.

Kleinman, M. A. R., Marijuana: Costs of Abuse, Costs of Control (NY:Greenwood Printing, 1989).

Levine, J. M., et al., "The Demand for Higher Pedagogy in Three Mid-Atlantic States," New York Economic Review 18 (Autumn 1988):3–20.

Matas, A., "Need and Acquirement Implications of an Integrated Transport Policy: The Case of Madrid," Transport Reviews, 24:2 (March 2004): 195–217.

Rizzo J. A., and David Blumenthal, "Doctor Labor Supply: Do Income Effects Thing?" Journal of Wellness Economic science 13(four) (Dec 1994):433–453.

Ross, H., and Frank J. Chaloupka, "The Effect of Public Policies and Prices on Youth Smoking," Southern Economic Journal 70:four (April 2004): 796–815.

Saffer, H., and Frank Chaloupka, "The Demand for Illicit Drugs," Economical Enquiry 37(three) (July, 1999): 401–411.

Suits, D. B., "Agriculture," in Walter Adams and James Brock, eds., The Structure of American Manufacture, ixth ed. (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, , 1995), pp. i–33.

Tauras. J. A., "Public Policy and Smoking Cessation among Young Adults in the United states," Health Policy, 68:3 (June 2004): 321–332.

Elasticity Measures The Responsiveness Of,

Source: https://open.lib.umn.edu/principleseconomics/chapter/5-3-price-elasticity-of-supply/

Posted by: alstonculam1943.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Elasticity Measures The Responsiveness Of"

Post a Comment